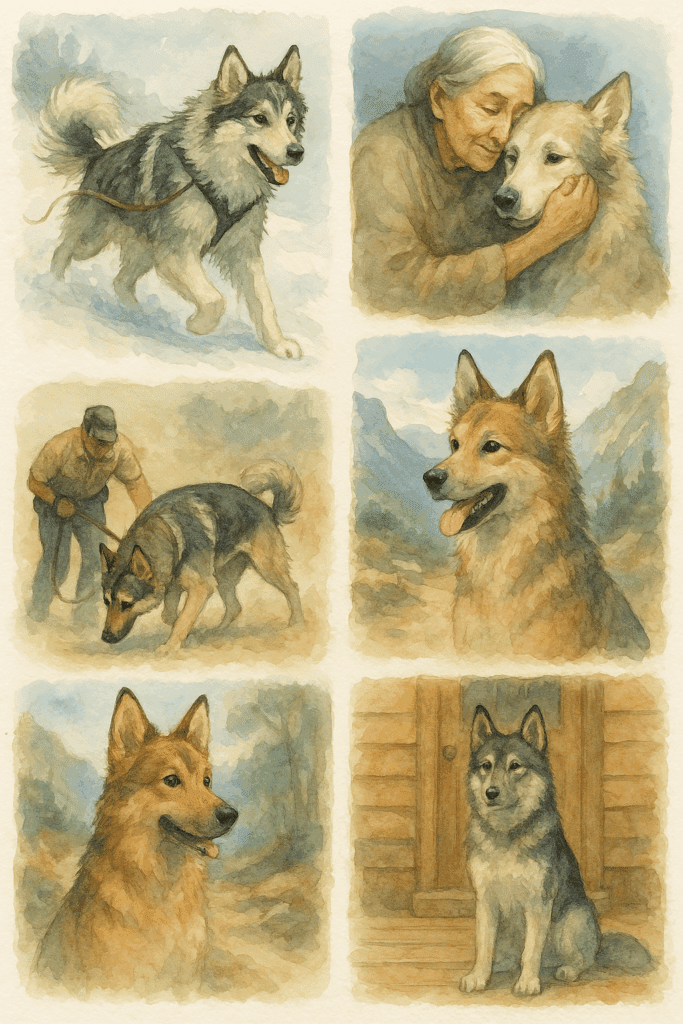

The Native American Indian Dog (NAID) is a breed surrounded by mystery, controversy, and confusion. From claims of ancient DNA to accusations of wolfdog ancestry, the internet is filled with conflicting narratives. But at the heart of this breed is something much deeper: a sacred purpose, a spiritual legacy, and a modern mission to reconnect people with animals, the land, and themselves.

In this article, we’ll separate the facts from the fiction and explore the real history of the NAID—not just as a breed, but as a movement.

Why This Story Matters

The NAID is more than a dog. For many of us, it’s a teacher, a guide, and a reminder of how humans were meant to live with animals—not above them, but beside them. And yet, with the growing popularity of the breed, misinformation has taken root.

From breeders making false claims to online groups perpetuating myths, it has become difficult for the public to know what the Native American Indian Dog truly is. This matters not just for the integrity of the breed, but for the people whose cultural connections are being misrepresented or exploited.

Dogs in Indigenous Cultures: What We Know

Long before colonization, dogs played important roles in many Native communities. In the tribes all over Turtle Island, dogs were not pets in the modern sense, but family members, workers, spiritual allies, and ceremonial beings.

Some carried packs and pulled travois; others guarded homes and sacred places. Some were included in naming ceremonies, purification rituals, and vision quests. Dogs were often viewed as protectors and spirit messengers.

There is no single “ancient NAID bloodline” that survived colonization intact, but there is no question that dogs were spiritually and culturally significant to many Native peoples. This understanding lays the groundwork for what the modern NAID represents.

The Creation of the Modern NAID

The breed we know today as the Native American Indian Dog was shaped by a breeder named Karen Markel. Her intention was to create a dog that, as closely as possible, represented the early Native dogs in appearance and temperament: intelligent, intuitive, emotionally bonded, and highly capable.

Karen’s early breeding stock included several malamutes, huskies, and low-content wolfdogs. There were additional one-time inclusions of Chinook, Samoyed, Belgian Tervuren, and Collie, and a few careful introductions of Shepherd to increase recall and biddability. However, what is often overlooked is that many of the foundational dogs in the program were tribal dogs, collected from various Native communities including Inuit, Cherokee, Blackfeet, Ojibwa, and Shoshone families. These dogs, while not directly traceable through written records, visibly carried characteristics distinct from mainstream northern breeds.

Old photographs of these foundation dogs reveal forms and expressions that closely resemble early Native working dogs—a lineage that may not be fully mapped through modern genetic tools, but is visibly and functionally preserved.

So while we do not claim that modern NAIDs are identical to pre-colonial Indian dogs, we do understand that the breed carries authentic ancient lineage, rooted in tribal dogs and preserved through intentional breeding.

Importantly, these dogs were selectively bred over generations, and modern NAIDs should no longer carry any recent wolf DNA. In fact, NAIDs verified by the Native American Indian Dog Preservation Project (NAIDPP) test negative for recent wolf content through UC Davis testing.

Myths, Misuse, and Misinformation

Several misleading narratives have emerged about the NAID:

“They are direct descendants of ancient Native dogs.”

While inspired by historical Native dog types, modern NAIDs are a preservation effort that includes both ancient tribal stock and selective breeding. The breed’s connection to Native lineage is real, but not unbroken.

“They are all wolfdogs.”

Some breeders crossed modern NAIDs with wolfdogs or dog breeds like the Tamaskan, that may test positive for wolf content, which has led to confusion. These dogs often test positive for gray wolf on Embark, but dogs verified through NAIDPP and UC Davis do not have recent wolf ancestry.

“All Indian Dogs are the same.”

With multiple breeds (AID, NorthAID, NAID) using similar names, the public has trouble distinguishing between them. Each has its own origin, development, and standards.

Why the NAID Still Matters

Despite the confusion, the Native American Indian Dog continues to fulfill a vital role. It is a breed born not only from genetics, but from intention. These dogs are emotionally intelligent, spiritually attuned, and capable of forming powerful relationships with the people they are meant to guide and protect.

They are used today as:

- Service animals

- Therapy dogs

- Emotional support companions

- Guardian Dogs

- Spiritual allies in healing work

What makes them special is not just their ancestral ties, but their present-day purpose. These dogs are medicine in motion.

Preserving the Truth

At the Native American Indian Dog Preservation Project (NAIDPP), we are committed to:

- Genetic verification through UC Davis and Ancestry Know Your Pet

- Transparent lineage tracking with over 1,000 dogs in our registry

- Rescue and rehab of mislabeled or mishandled dogs

- Public education on what the NAID truly is—and what it isn’t

We believe that the future of this breed depends on telling the truth. Not the most marketable story, but the most meaningful one.

Final Thoughts

The Native American Indian Dog is not ancient in an unbroken bloodline, but it is deeply connected to the ancient dogs of Native communities through intention, form, and lineage. It carries forward the legacy of our relationship with the land, the animals, and the sacred connection between all living things.

By honoring the truth about this breed, we honor the people, animals, and traditions that inspired it. And we plant seeds for something enduring, something real, something rooted.

Let that be the story we pass on.

Want to learn more about NAIDs, verify your dog’s ancestry, or get involved with our preservation efforts? Visit NAIDPP.org

2 comments

Lisa

I thought the Carolina Dog was the indigenous dog of North America?

administratoir

Thank you so much for your thoughtful comment. You’re absolutely right that the Carolina Dog plays a meaningful role in the story of North America’s Indigenous dogs. Often called “America’s Dingo,” the Carolina Dog is a fascinating landrace with genetic links to ancient East Asian dogs—supporting the idea that it descended from the dogs who migrated alongside early Indigenous peoples. Its survival in the wild for centuries has preserved traits that are incredibly valuable in understanding what pre-contact tribal dogs may have looked and behaved like, especially in the Southeast.

That said, it’s important to recognize that the Carolina Dog represents just one regional expression of Indigenous dog types. The Native American Indian Dog (NAID), which we focus on here, is a modern composite breed created to reflect a broader spectrum of the dogs once used by Native peoples across various tribes and regions. While the NAID is not a direct, unbroken bloodline going back thousands of years, it was originally developed using several primitive and tribal-type dogs—including the Carolina Dog, Inuit dogs, and other aboriginal lines.

At the NAID Preservation Project, our mission is to honor that vision while correcting misinformation and holding the breed to a higher standard—genetically, behaviorally, and culturally. We DNA test all our dogs, monitor inbreeding levels, and have worked for years to identify and verify which lines carry the original genetic markers. We also actively combat the myth that these dogs are wolf hybrids, which has unfortunately been perpetuated by some breeders and misinformed sources.

So while the Carolina Dog may be the closest remaining wild example of one type of Indigenous dog, the NAID is a carefully guided effort to preserve and carry forward a legacy that spans multiple tribes, regions, and working roles. They are not the same, but they are connected—and both deserve a place in the larger conversation.

I really appreciate you taking the time to engage with the history and share your thoughts. It’s conversations like this that help protect and preserve the truth.